Process Engineering: Tools of the Trade

January 24th, 2023

The phrase “process engineer” can have vastly different meanings in different contexts. Depending on the nature of the product, the work to support and improve the processes involved differ wildly. The key skills, responsibilities, and the day-to-day activities for a process engineer in a medical device company are very different from one who works in a pharmaceutical or chemical setting, for example.

Process engineers may also focus on different stages of the product development cycle - some are involved early on to ensure the product and process design are manufacturable and scalable in the New Product Introduction (NPI) stage, while others focus mostly on incremental improvements on an established production line. Some companies call the latter “production engineer”, or “manufacturing engineer”. Regardless of the focus, process engineers are the leaders who embody the spirit of continuous improvement. Think of them as the hub that enables the wheel to turn smoothly in your day to day work on the laboratory or production floor.

Below we will discuss, in general terms, a few key aspects of a process engineer’s work in an example coffee-making setting. The underlying concepts are applicable regardless of what field:

Process Development and Improvement

The process engineer serves as the bridge between research and development (R&D) and operations. While a hypothetical new technology that works well 20% of the time in the laboratory may be lauded as a game-changer from a technical innovation standpoint, a 20% yield is likely not practical or economically viable from a commercial product perspective. The process engineer strives to close this gap by deeply understanding how process inputs affect process outputs, and hence, quality of the product. The goal is to stabilize the manufacturing process so that its output is predictable. This can be challenging without a thorough understanding of the process, especially when manual work is involved, and when subtle environmental changes can affect process behavior.

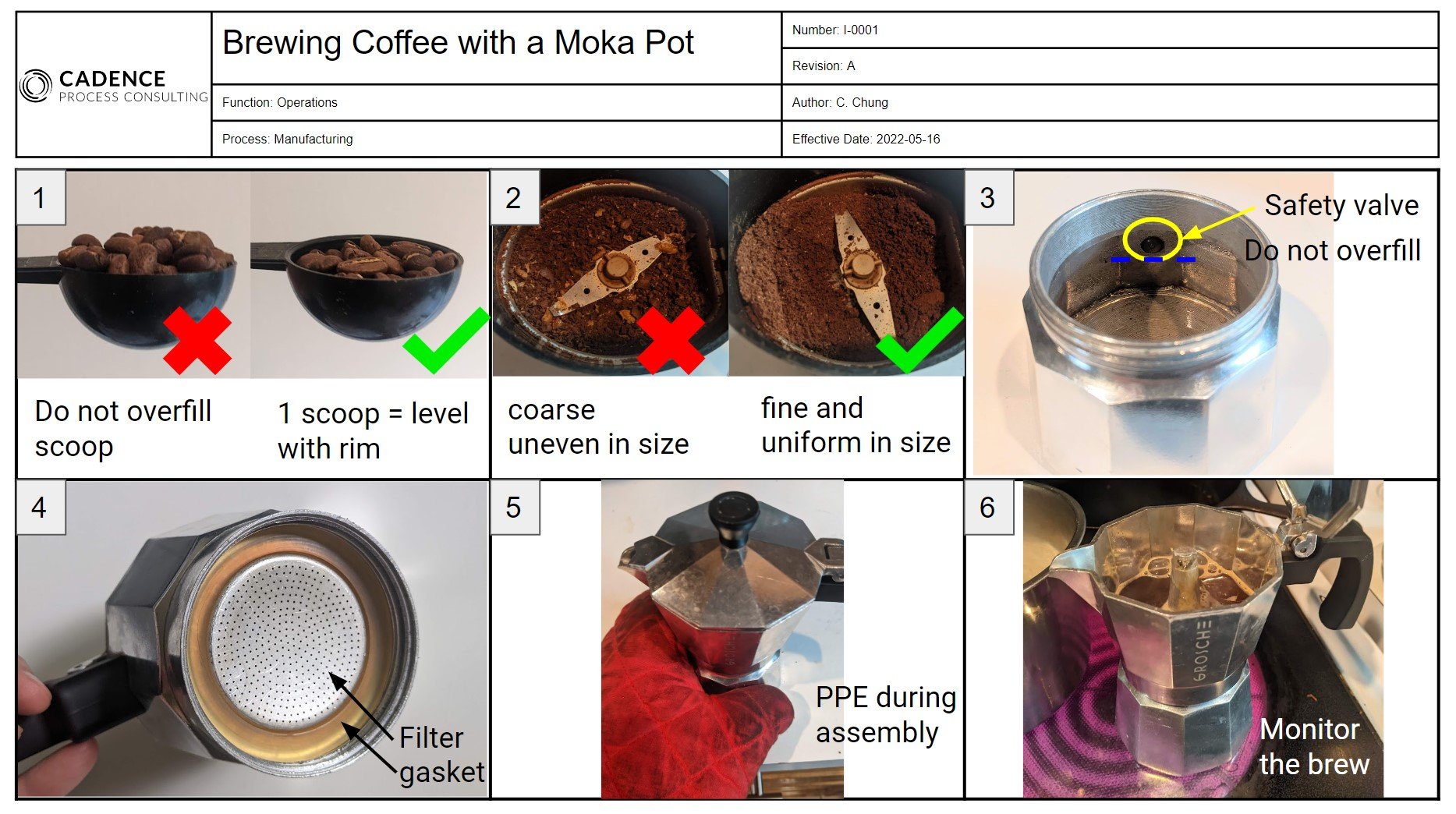

Before improvements can be made, we need to establish a standard, a baseline condition that reflects the current state of affairs. This is the basis upon which the team will improve. For example, a process engineer may capture the current coffee making process in a work instruction document.

To ensure that the coffee is consistently of high quality (ie. the right temperature, has strong aroma and caffeine concentration) despite being made by different people at different times of the day in different locations, the engineer will need to:

Tease out the important factors that impact coffee quality, and

Implement methods ensure that these factors stay consistent all the time

Ensure work is done safely

For example, suppose caffeine concentration is dependent on the coffee bean amount, coffee ground size, and water volume, then the process engineer may lead efforts to find the best amount and ground sizes to use, and implement ways to ensure that the acceptable standard is clear and repeatable to everyone who performs the process. One way to do that is to make standards visible. Below is an example of a visual aid that may be posted at the worksite as a reminder:

Other ways a process engineer can further make the process easier and more consistent include:

Fixtures or markers that ensures a tight gasket seal

Mistake-proofing (poka-yoke): discard wrong-sized measuring spoons so the user will always use the right size to measure coffee beans

Automation: a programmable espresso machine will dispense the desired amount of ground coffee, water, and brew them at specified temperature and duration

Democratize Training

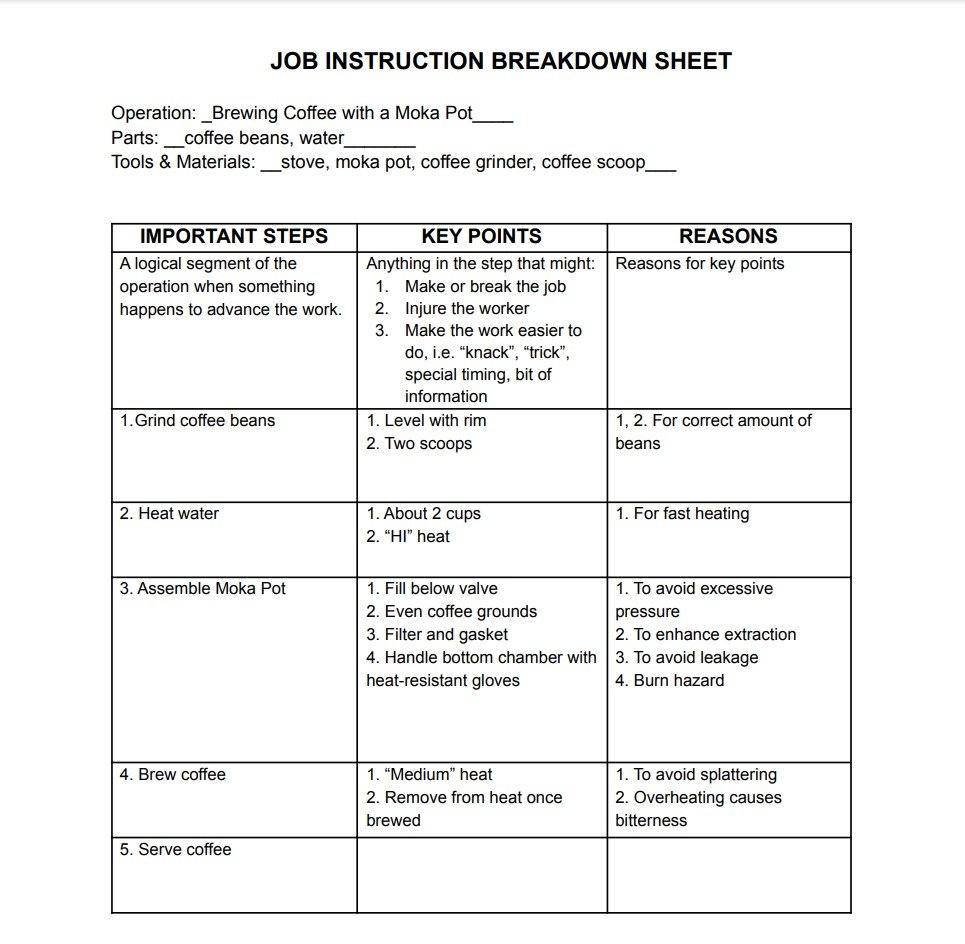

Complex processes that are not well understood are often viewed as a black box. Sometimes even the experts most familiar with the process rely on their “magic touch” or intuition to run the process without knowing why it works. This is dangerous - not only is it hard and time-consuming to train new employees to perform something that is considered as a craft or art, there is also the risk of the training content evolving out of control when tribal knowledge is passed from one person to another, like in a game of telephone. The process engineer leads the team effort to uncover and understand key details to be included in the training, and to standardize training content delivery.

The process engineer acts as a role model for the team in this collaborative effort to create and refine training content. In essence, they lead the team in helping the process expert (often a senior technician) become a great trainer; instead of being the only one who can do the job well, the process expert coaches other team members to perform at the same expert level through an efficient training process. The impact on team dynamics cannot be overstated - under the guidance and facilitation of a process engineer, the production team’s culture would gradually shift from competitive to collaborative. This goes a long way in enabling further process improvements.

In practice, the process engineer can leverage the Training Within Industry (TWI) Job Instruction framework to engage the team and develop training content. Below is an example of a Job Instruction Breakdown Sheet for making coffee:

Process Monitoring

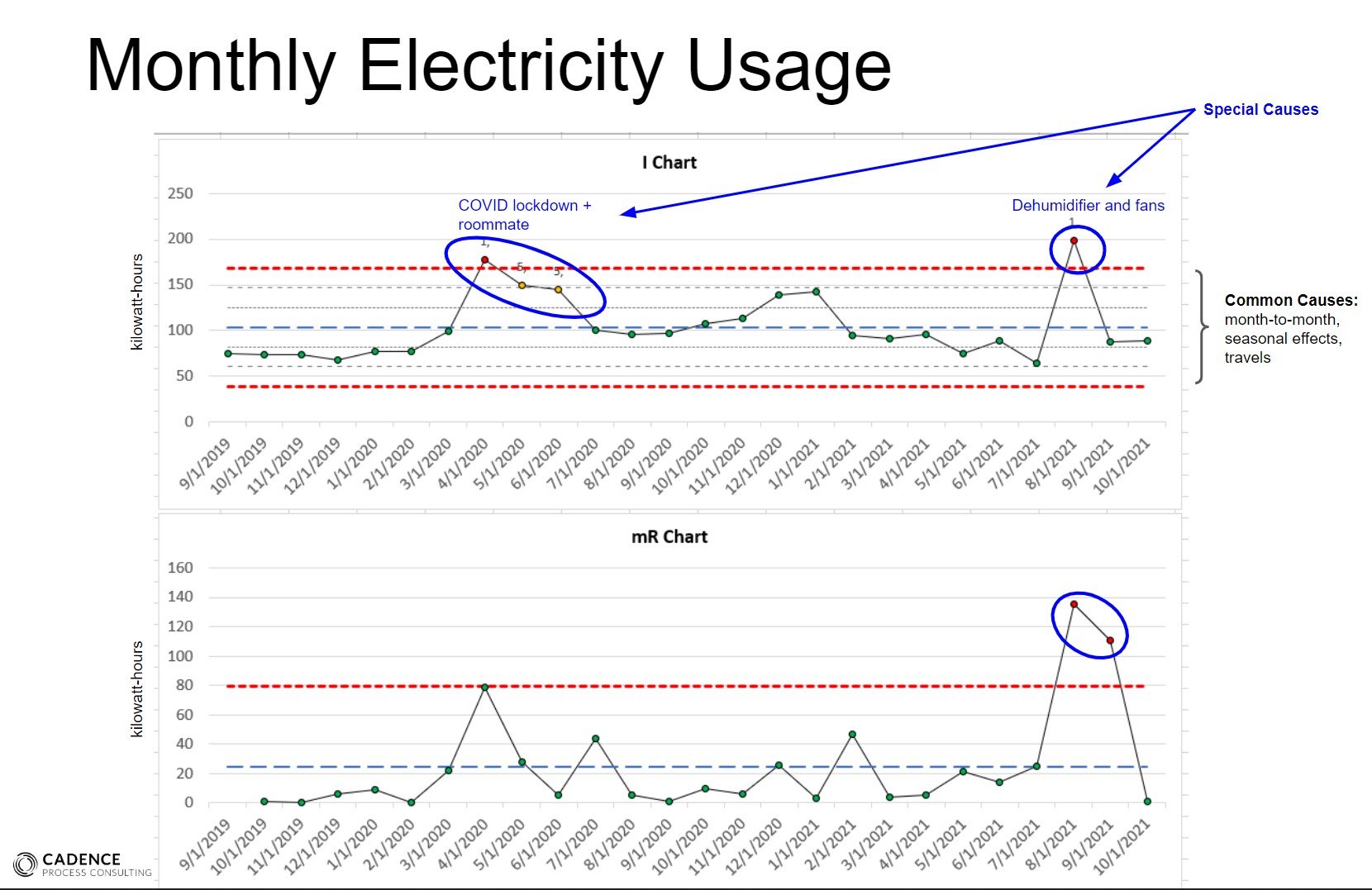

Once a process is running routinely, a process engineer would keep an eye on key process parameters to ensure that it is behaving as expected, and that the instructions and training are adequate. Detecting unexpected process behavior promptly is very important - not only do we want to address possible quality issues as early as possible before product issues make it to the customer, but also we want to take problems as opportunities to make further improvements.

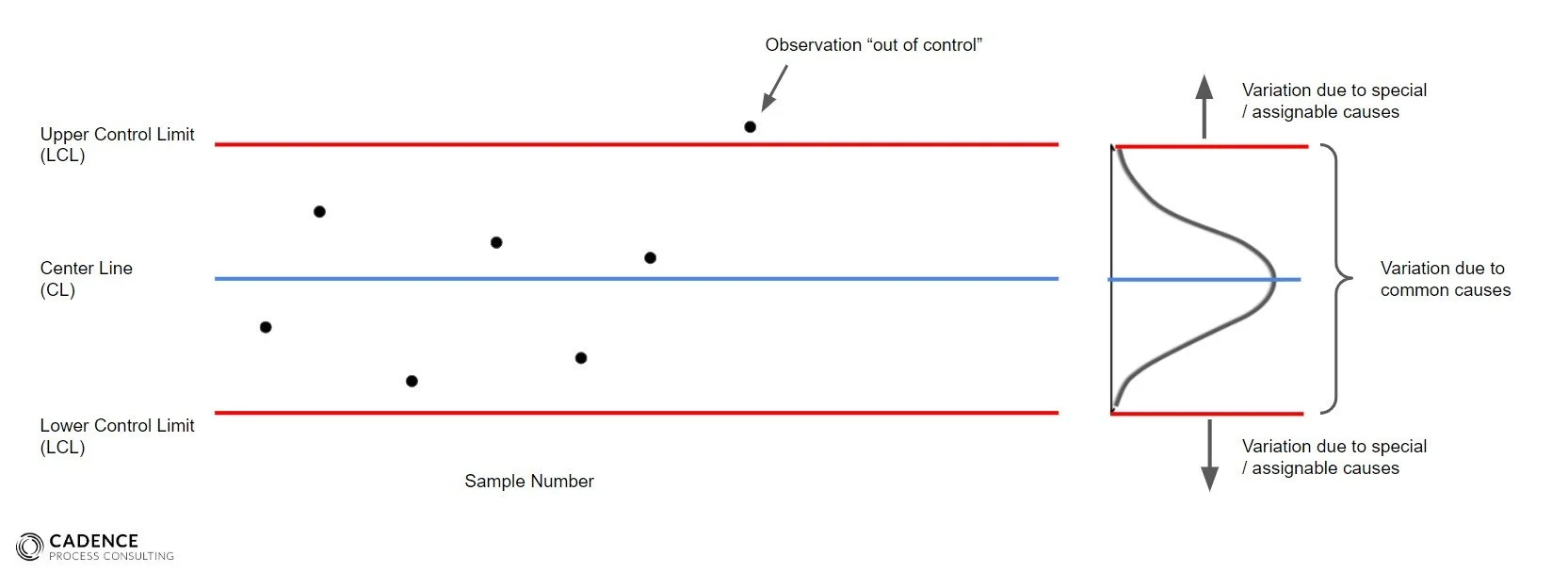

Control chart is a great tool to visualize process (in)stability - it helps the user distinguish “common cause”, or expected variation inherent in the process, and “special cause”, or variation due to assignable causes - this can be a sign that the process is drifting “out of control” and needs to be actively addressed.

The control limits, in red below, are calculated from data collected from the process, based on the spread of data over time, and shows the “expected” variation of the process. The control limits, and additional pattern-driven rules, flag special causes that deserve additional attention.

Below is actual electricity usage data spanning two years. Although there is month-to-month variation, two special events were flagged by the control chart: one is the COVID lockdown, and the other was a water damage which resulted in a spike in electricity consumption as a part of the mitigation process.

We hope the above examples have provided a well-rounded overview of what a process engineer works on, and the tremendous value that a great process engineer can bring to your company. It is an essential role that can accelerate progress toward operational excellence - all the way from product development to the day-to-day manufacturing and continuous improvement efforts.